Alexander Moffat Painting As Arguments Five Decades of Political and Cultural Change in Scotland

Centred on the work of Alexander Moffat this exhibition opens enquiries into important changes and achievements in cultural expression and education, artistic means of production and dissemination in Scotland and their international contexts. A complementary programme of film screenings, talks and panel discussions will allow for wider reflection and public engagement.

The period from 1960 onwards saw major cultural change in Scotland and throughout the world. Moffat was directly involved as an artist-activist, a curator and a teacher. He opposed current establishment conventions, curated and exhibited work by young Scottish artists and taught new generations with a major and continuing influence. His main aim as an artist, curator and writer has been to place Scotland and Scottish art in a relationship with the rest of the world.

As the country prepares to answer the question of whether it wants self-government or not, we ask what contribution have the visual arts made in taking us to the point where a referendum on independence is even thinkable, no matter the outcome. What has been the role of the “success story” of Scottish art in increasing self-awareness of Scotland’s cultural distinctiveness? Have our artists helped to build confidence amongst the people of Scotland and banish the old inferiority complex, the “cringe”? What are the cultural arguments for, or against, independence?

Exhibition views

Exhibition works

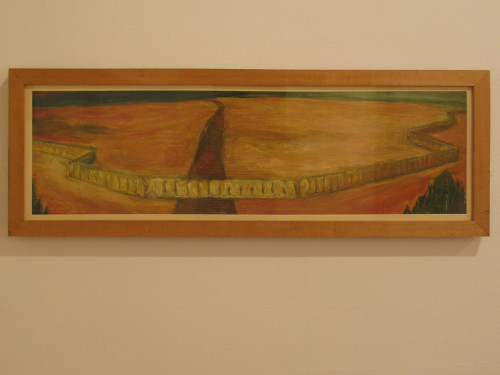

Picnic at the New Bridge, 1963, Oil on Board

In July 1963 I travelled to the South of France to visit the Léger Museum at Biot and the Picasso Museums in Antibes and Vallauris. It seemed to me that both Picasso and Léger held the key to a figurative language of painting that was both modern and capable of being explored and developed.

'Picnic' was completed on my return and first shown at the Edinburgh Festival in August 1963. The new bridge referred to is the Forth Road Bridge, a symbol of modernity and a sign that Scotland was moving forward from the drabness of the immediate post war period. As such, the painting was an optimistic statement.

The young dancing black girl, however, reflects my awareness, as a jazz fan, of the Civil Rights movement in the US, then gathering momentum with many of the great jazz musicians of the period actively involved. The arrest of Nelson Mandela and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa were also huge issues at the time.

Alan Bold, 1969, Charcoal on Paper

Ronald Stevenson, 1969, Charcoal on Paper

Mary Maclver, 1988, Pastel on Paper

Berliners 3, 1978, Oil on Canvas

The three large paintings entitled 'Berliners' began with a portrait of Neal Ascherson in 1976 that included quotations from George Grosz, setting Neal unequivocally in Berlin, where he had been based in the 1960s while working as the Observer newspaper's East European correspondent. Afterwards the thought occurred to me that the idea could be further developed in a series of 'expanded' group portraits… contemporary history paintings if you like.

In Berlin, history is almost tangible… in particular, the history of the twentieth century. Berlin has played host to all the movements that have uplifted and afflicted German and European history. No other city has played such a crucial part in shaping the political and cultural life of Europe.

In ‘Berliners 3’ Neal is situated in the Berlin of the late 1960s, the period of student revolt against the prevailing political status quo. His companions are Rudi Dutschke and Ulrike Meinhof. The other figures are mainly derived from Grosz, reflecting the previous historical period of revolution in Berlin in the aftermath of World War One (1918-19). Rosa Luxemburg is seen in the top right of the painting while below a prostitute is engaged in conversation with a wealthy client. For the artists of the Weimar Republic prostitution was a salient symbol for capitalism. In the foreground we have George Grosz himself - the artist as a hard-bitten cynical witness.

In the top left corner the shooting of the student Benno Ohnesorg by the West Berlin police in 1967 is depicted. This was the catalyst for the unrest that was to follow in 1968. On a table in front of Ascherson is a book, the collected works of Georg Buchner (1813-37). Buchner was a student of medicine who threw himself into revolutionary politics and before his death at the age of 23 published three remarkable plays, Danton's Death, Lenz and Woyzeck. The central figure is of a broken, disillusioned soldier retuning from the trenches… what kind of fate lies in store for such a human being?

With their protests the '1968 Generation' set post-war Germany on a new path. Ulrike Meinhof, however, resorted to a belief that only violence could overturn what she came to believe was still a fascist state. As a member of a terrorist group known as the Red Army Faction that murdered 29 innocent people between 1970 and 1979 she was eventually captured by the police and committed suicide in Stammheim prison in 1976. Four thousand people turned out for her funeral.

I intended the painting to pose questions about art and politics, revolutionary protest, extremist ideology, the repetitions of history, etc. - all issues that have been addressed by Neal in his long career as a journalist and in his writings about politics - issues we have to engage with in Scotland if we really aspire to becoming a European nation again.

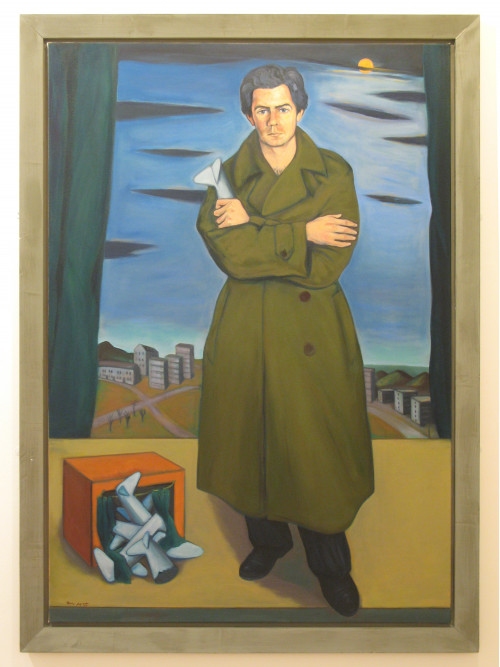

David Hosie, 1987, Oil on Canvas

I first met David Hosie (born 1962) when he was a student at Edinburgh College of Art. Unusually for a young Scottish painter he had studied the great Italian moderns, De Chirico, Carra and Sironi, often grouped together as the leading exponents of the Pittura Metafisica movement. Hosie was interested in the isolation of the individual, the communication of the disquiet he found in the vast housing schemes surrounding both Edinburgh and Glasgow. Built as a post war socialist solution to the dilapidated inner city slums, these had by the 1970s turned into neglected zones, populated by an unemployed underclass. Hosie's paintings were a reaction to the Scotland of the 1980s with its huge contrasts of wealth and poverty, of moral hope and underlying violence. I depicted him as a participant in one of his own paintings.

From The Contest – Salisbury Crags series, The Contest, 2014, Charcoal/Pastel on Paper

In the summer of 1988 I filled a sketchbook with drawings of Arthur's Seat and the Salisbury Crags, the volcanic ruins that loom over Scotland's capital city. I was aware of their literary significance - the setting for James Hogg's 'Confessions of a Justified Sinner' and Walter Scott's role in the creation of the 'Radical Road'. My first thoughts, however, were concerned with Robert Burns and Edinburgh and I asked myself what Burns - who as a patriot and radical republican - might make of Scotland today and especially the current political situation. As Tom Nairn put it at that time "since the row over participation in the Constitutional Convention… once that short-lived unity over rational progress towards our own state had been destroyed, what was left apart from an intensifying struggle between two hirpling lunatics trying to smash each others crutches?"

I proceeded to make a number of works depicting two battling protagonists. Specific Edinburgh landmarks such as the Calton Hill, St Andrews House, the former Royal High School, the Burns Monument, were deployed for their symbolic qualities and as a setting for the struggle for Scottish liberty, "liberty's in every blow". The viewpoint used was that of Salisbury Crags.

I returned to the theme in the summer of 2013 in an attempt to find further resonances at a time of national debate and the coming referendum on Scottish independence.

From Picasso's Vollard Suite series, Sculptor and Model by a Window, 2010, Oil on Canvas

From Picasso's Vollard Suite series, Blind Minotaur Led by a Girl with Fluttering Dove, 2008, Oil on Canvas

Picasso was an artist who at certain key moments during the 20th century made a stand for humanity… the painter of 'Guernica' in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War and later as a member of the French Communist Party using his great wealth to assist both striking French coal miners and Spanish refugees from Franco's regime.

I have long admired the great series of 100 etchings made between 1930 and 1937 commissioned by the dealer Ambroise Vollard… and as many of the images were never turned into paintings by Picasso, I decided to make paintings of several of the etchings in the way a composer might 'orchestrate' a work written originally for piano, in the manner of Caplet's or Koechlin's orchestrations of Debussy's piano compositions.

James Robertson, 2012, Charcoal/Pastel on Paper

Sorley MacLean, 1986, Lithograph

Tom Nairn, 2012, Pastel on Paper

The End of History, 1990, Oil on Canvas

Painted in the aftermath of the fall of the Berlin Wall - I visited Berlin in January 1990 and began a group of works I called ‘Historical Landscapes’. As a witness to history being made there were many questions to ponder. Was this really an end to the Cold War and all that went with it? Had we really experienced the triumph of capitalism? It was almost impossible to grasp the massive change to the world I had grown up in and inhabited all of my life. I knew immediately I would have to paint about all of this…