New Aberdeen Bestiary The Lizard - Carla Filipe

The Lizard is the fourth exhibition in the New Aberdeen Bestiary, showcasing work by Portuguese artist Carla Filipe, realised in collaboration with printmakers Neil Corall, Jodi Le Bigre and James Vass. The exhibition explores popular lore surrounding the sardão, a species of lizard.

Carla Filipe’s wide-ranging artistic practice engages with the history of industrialisation and colonialism, and with self-organised ways of making a living, through a mix of archival work and autobiography. She creates installations which include prints that combine text, imagery, and objets trouvés.

The sardão is found in the Iberian Peninsula, Southern France and Northern Italy, also known as ocellated or jewelled lizard. The entry for ‘lizard’ in the Aberdeen Bestiary, the twelfth-century manuscript that the project is inspired by, describes other lizards such as the botrax, the salamander, the saura and the newt, but not the sardão.

What is the sardão like? The adult is 30 to 60 cm long (including the tail) and some specimens may reach up to 90 cm. It is usually greenish in colour, with a broad head and thick, strong legs, and long claws. According to the artist, the sardão is the terror of women in the countryside. During our first conversation, she spoke about a widespread folk tale which admonished girls, from a young age, not to go into the fields while menstruating, for the large lizard might attack them.

Similar tales and popular beliefs are crucial to Carla Filipe’s approach to the New Aberdeen Bestiary. This particular tale has interested Carla for a long time. In a work titled Família (2005), Carla evokes a wariness about the countryside, stating ‘I hate animals!!! I have so afraid!!! Detesto o campo pelos animais!’ which translates to I despise the countryside because of the animals. This fear of wild animals for her was largely a result of folk tales that pit ‘good,’ useful animals, such as domesticated animals, against ‘harmful’ ones, such as wild ones. Carla, having repeatedly heard these stories as a child, took them as truth. For her, they go hand in hand with a feeling of terror. In one of the prints in the exhibition, she recalls one of the stories that originated her terror of the sardão: ‘When I went to see my mother, and I was menstruating, I got stressed... I would go jogging, I would take sticks with me and some stones in my pockets, oh...Those tall spring herbs that blocked any path... 30 cm. That's where the biggest rush took place, besides being the season for ticks, and all the animals. I got to my mother's side with adrenaline running high. She never understood why she was so stressed, she never imagined that all the stories I heard as a child that made me afraid of all animals.’

These stories about the sardão are corroborated by other people, in different regions of Portugal. Women grow older afraid of the sardão because, as Carla again states in Família (2005), '[the] lagarto defende o homem,' lizards protect men. But is there a scientific explanation for this belief? Of course not. Put in a different way, is there evidence of women being attacked by the sardão? Yes, I have been told. Possibly, this is the reason why, in Portuguese, ‘sardão’ is also a colloquial word for male genitalia.

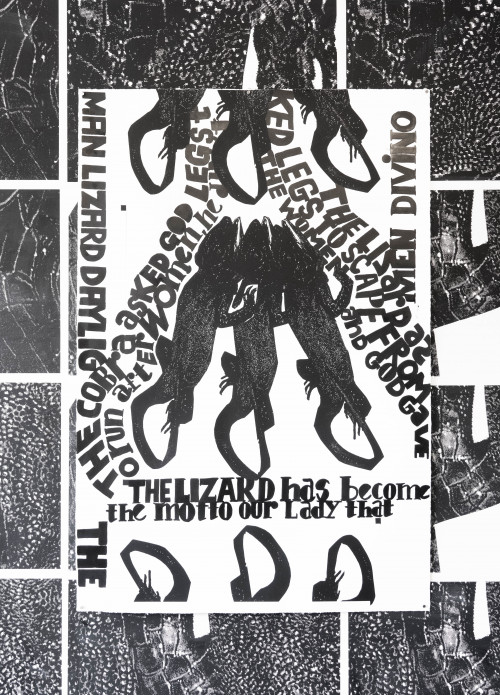

According to another Portuguese saying, a snake asked God to give it legs to run after women and God did not give them to it; therefore, snakes crawl. But when the sardão asked God to give it legs to run away, God did. Many Portuguese folk stories are rooted in Christianity. Could the distrust Carla and other women have for the sardão be related to the Biblical relationship between Eve and the snake, where women come to be associated with snakes.

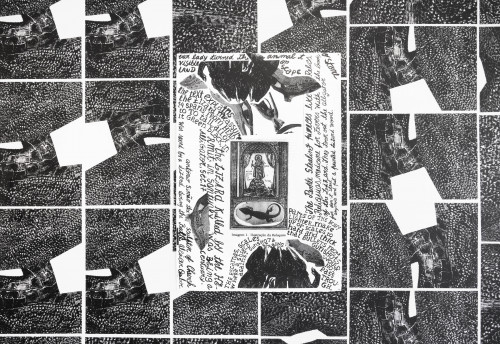

Symbolising women and men respectively, the snake and the lizard stand as complementary opposites. The relation of unity and opposition between dualities is crucial to The Lizard.' As the lizard is abstracted into its constitutive elements, into fragments of skin and eye, it could also be seen as a snake; the two morph into each other as if by a trick of the eye. Carla Filipe’s proposition in The Lizard reframes language in terms of form and meaning, creating an idiosyncratic idiom with a strong written narrative and a self-reflective element. This is visible in the intertwined use of two languages, Portuguese and English, and the use of handwriting on top of print.

The grammatical construct ‘and/or’ might be used to illustrate the nuances of Carla’s language. What happens when we say snake and/or lizard? It indicates that one or more (or even all) of the instances it connects may occur. It is not simply snake and lizard, or snake or lizard, but snake and/or lizard, meaning that while they are in opposition (or), they are also complementary (and). This happens by creating a tension that is not easily undone.

And/or is sometimes criticised as an ‘ugly’ and ‘Janus-faced’ construct, a device that damages a sentence leading to confusion or ambiguity. Rather than clarity, Carla Filipe is here engaging in confusion and ambiguity as a way of questioning hierarchies of knowledge and inherited distinctions between dualities of female and male, of lore and science. In Filipe’s exhibition, there is a decisive move away from clear dichotomies and towards more complicated and composite visions of the world.

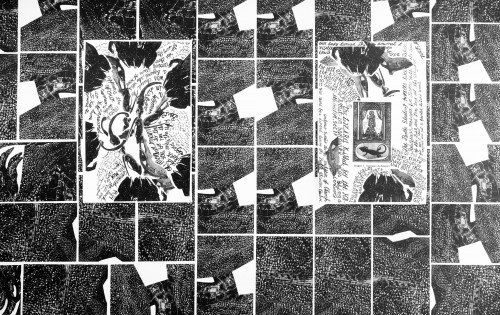

The works in the exhibition reflect the artist’s disquiet, her disdain for accepted and ‘proper’ ways of doing. During her residency, Carla worked across a variety of printmaking techniques, from lithography to relief printing and screenprinting. The works employ a variety of papers, from fine printmaking paper to newsprint, under the guidance of our printmakers but remaining very physically involved in the composition of the works. Her way of composing prints is organic, decided on the fly, then finished by hand, developing several linguistic and calligraphic quirks in the process. The results of her rule breaking are irreverent and indomitable images, often resorting to humour.

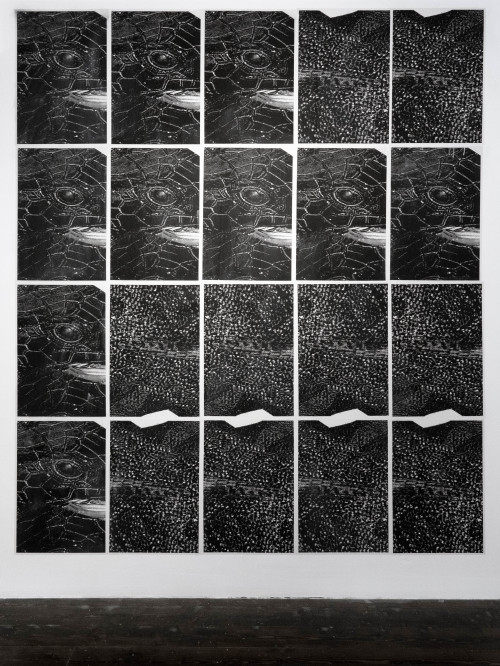

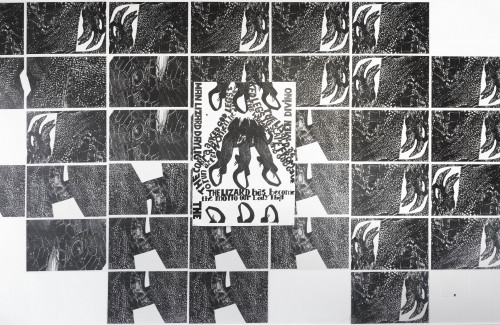

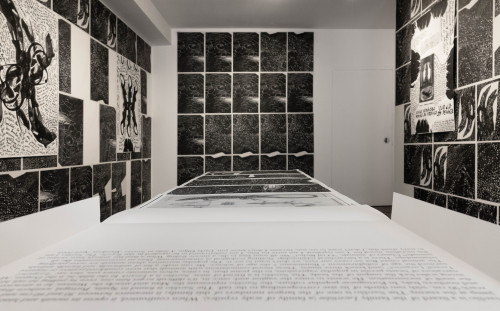

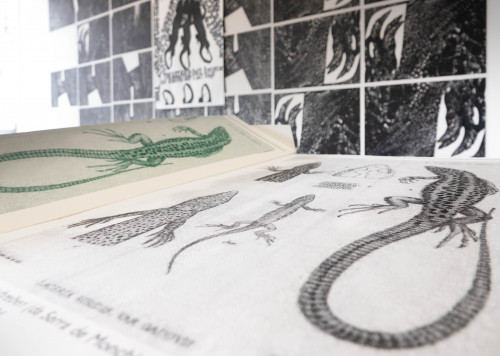

The space of the gallery is covered by over 100 hand-printed black and white wallpaper tiles depicting reptilian eyes and skin, resembling constellations. Arranged on top of those, there are six prints, completed by handwritten text. In addition, there is also an artist’s book, a publication carrying several aspects of the exhibition: a text about the sardão, the reptilian eyes and skin that cover the walls, a scientific drawing of the animal, and a folded relief-printed cover holding these materials. With the artist book, Carla’s intention is to make an affordable fine art publication that will outlive the exhibition.

This exciting project was conducted with extreme attention to detail, testing the limits of what we as a studio can do in terms of printmaking, as well as what we perceive as fine art printmaking. Our inherited knowledge about what printmaking can or cannot be was under fire, questioning the value of what we do, but also whom we do it for.

Similarly, it challenged an accepted relation of opposition between domesticated and beastly, between scientific knowledge and popular belief. Rather than being an anomaly, this Janus-faced approach to printmaking and to the (New) Aberdeen Bestiary might have resulted in a totally new species.

[exhibition photos by Robert Page]

About Carla Filipe

Carla Filipe (b.1973) is an artist working and living in Porto, Portugal.

She was co-founder of artist-run spaces Salão Olímpico (2003-2005) and Projecto Apêndice (2006), both in Porto. She has worked and exhibited in several high-profile institutions across Europe. She has undertaken residencies at Acme Studios, in London, AIR Antwerpen, Antwerp, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation (Captiva, Florida) and the Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna.

She has exhibited as a solo artist in some of Portugal’s most important museums, such as the Serralves Museum, MAAT, and the Museu Coleção Berardo. Solo shows outside Portugal include exhibitions in the Krinzinger Projekte, Vienna; AIR Traces, Antwerp; and tranzitdisplay, Prague. She has taken part in group exhibitions in institutions including SESC Pompeia (São Paulo, Brazil), Haltingerstrasse 13 (Basel, Switzerland), Museo Reina Sofía (Madrid, Spain), and Spike Island (Bristol, UK). She also participated in the 4th Ural Industrial Biennial of Contemporary Art in Ekaterinburg, Russia, the 13th Instanbul Biennal, and Manifesta 8 in Murcia, Spain.

Working in a variety of forms and media, including drawing, printmaking, textiles and installation, she has also produced an extensive catalogue of artist books and publications. Of these, is available in English: ‘An Illustrated Guide to the British Railway to my Study,’ texts and photographs by Carla Filipe, cover texts by Ulrich Loock and Miguel von Hafe Pérez, published in Portuguese and English, edition of 500, published with support from the Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2010. Her most recent work, ‘Poemas oblíquos, binoculares e matinais,’ is an artist book with texts and illustrations by the artist, realised in linocut and letterpress, printed at workshop Edições 50Kg, edition of 50, Porto, Portugal, 2022.